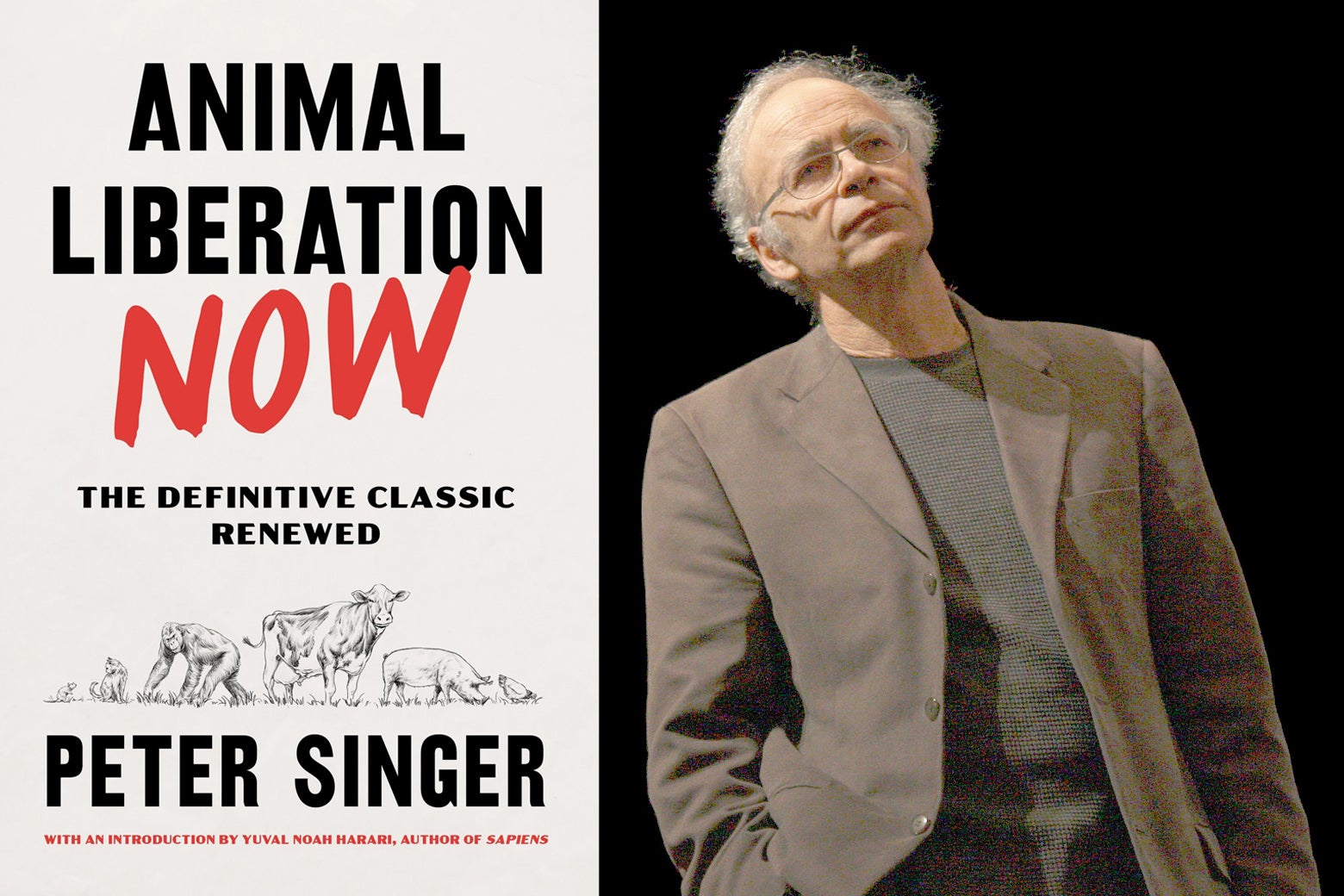

Gabfest Reads is a monthly series from the hosts of Slate’s Political Gabfest podcast. Recently, Emily Bazelon spoke with author Peter Singer about the importance of veganism for climate change and stopping animal cruelty. Singer’s book Animal Liberation Now was just rereleased and updated.

This partial transcript has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Emily Bazelon: What about the environmental benefits of ceasing to produce and slaughter and eat all kinds of flesh in the way that we’ve been doing? At one point in your book, you say that people who care about the well-being of humans and the preservation of our climate and our environment should become vegans for those reasons alone. So why, what’s at stake here? What’s the impact that has just become much more apparent in our era?

Peter Singer: Well, the major impact that of course I didn’t really know about in 1975 was the contribution of the meat and dairy industry to climate change. And that’s a very substantial contribution because methane is such a powerful gas in heating up the planet, especially if we’re just looking at say, a short period, like 20 years, which many experts say is the time we have to get down to zero emissions. Methane is over 80 times as powerful as carbon dioxide over a 20-year period. And people don’t often realize that because people talk about its effect over a century and it does break down faster than carbon dioxide. But if we only have 20 years to stop doing disastrous things to the climate, then cutting out methane is the easiest thing to do. And the way to do that is to stop eating products particularly from cows and sheep because they are the biggest producers of methane.

And we don’t need new technologies, we don’t need new batteries, we don’t need to build a new power grid, none of that. We just need to cut those things out of our diet. And if we all did that, we would make a big reduction in greenhouse gases going into heating up the planet. But in addition to that, a lot of people don’t realize that we grow a huge proportion of our crops, a large part of our agricultural land, is used to grow grains and soybeans to feed to animals, and that includes clearing the Amazon. The major cause of clearing the Amazon forest is either to graze beef cattle or to grow soybeans, to feed to beef cattle and to chickens as well. And some people say to me, oh, I don’t want to eat tofu because that’s soy and I know that the Amazon is being cleared for soy. But actually 77 percent of the world’s soy crop is fed to animals.

So, tofu and tempeh and soy milk are a very small percentage of the soy crop. And it’s really inefficient to do that because the cows use at least 90 percent of the food value of the grains and soy we feed to them just to keep their bodies alive, to keep their bodies warm, to grow bones and other organs that we don’t eat. So, we’re wasting probably 90 percent of the food value of those crops. And without that, we could allow much more land to revert to wildlife. We could reduce our impact on rivers and water because intensive farming is a major polluter of inland waterways. And of course there’s local air pollution as well. Anybody who lives anywhere near a factory farm will tell you that when the wind blows from the farm to them, it stinks and it also produces millions of flies.

I moved you into the land of consequences and practical impacts of current human habits on people as well as animals. I want to go back to the kind of basic ethical argument you’re making here because I think that’s really the main thrust of the book and its enormous contribution. And in some ways it’s kind of head spinning. You say pretty early on, many animals can feel pain. And I think we talked a little bit about why we know that even more now than we did in 1975. And then you also say there’s no moral justification for treating their pain as less important than similar amounts of pain felt by humans. And I think that step is still difficult for a lot of humans or maybe just for me. Can you walk us through that a little bit and how you arrived there and what it means?

I wish you were the only one that that argument was difficult for. I’d make a lot more progress. Unfortunately, it’s quite widespread, so I’m glad you gave me the chance to respond to that. My view is that the boundary line that we currently draw, in terms of who matters morally, is a boundary around our own species. If you’re a member of the species homo sapien, you matter morally; you have human rights. If you don’t, if you’re not a member of that species, then you don’t have human rights and you don’t really have any rights and you certainly don’t have equal moral status or anywhere near it. Some people will say, you have some moral status—we don’t want to see cruelty to animals, but they will accept that if there’s some human benefit, we can do things that cause an immense amount of suffering to animals.

I think that’s wrong. I’m not saying that it’s a similar in its impact, but it’s a similar structure of thinking to that of racists of the most blatant kind. For example, the white European imperialists who went to Africa and captured or bought slaves, transported them in horrific conditions across to the United States or to the British colonies in the West Indies and sold them there. And the attitudes of the people who then held them as slaves, that was also a dominant group, a powerful group saying, “we are the ones who matter; these other ones don’t really matter, or their interests don’t matter as much as ours. We can use them as we wish.” And they developed ideologies to justify that, to make them feel good, including references to the Bible, which they interpreted as saying that God has said that some of the children of Shem, I think it was, are suppose to be slaves to us.

We do something similar with animals. We also quote from the Bible saying, God has given us dominion over the animals and for centuries we’ve interpreted that dominion as saying it means we can do what we like with them. Pope Francis, to his credit in a recent encyclical, rejected that harsh interpretation of dominion and said, no, God makes us stewards of the animals. We need to look after them. Well, that’s progress. But the previous way of thinking still has a powerful impact.

And I just don’t see how species boundary can be a morally crucial distinction. I think that the late 18th, early 19th philosopher, Jeremy Bentham got it right when he said, “the question is not, can they reason nor can they talk, but can they suffer?” And I think that is the question as to how bad it is that we inflict pain on them. It depends on whether they can suffer and if they can, then similar amounts of suffering should be given the same weight, irrespective of the species of the being.