Ann Rule, the queen of true crime, has an unforgettable origin story. While volunteering at a suicide-prevention hotline in the early 1970s, Rule befriended a handsome younger co-worker. A few years later, that man, Ted Bundy, was arrested for kidnapping a woman and became the lead suspect in a series of murders for which he was eventually convicted and executed. Rule’s first book, The Stranger Beside Me, published in 1980, recounted Bundy’s life and crimes from the unusual perspective of the killer’s friend. Her first book was also her first bestseller, inaugurating a 35-year reign that produced 35 New York Times bestsellers in the true-crime genre.

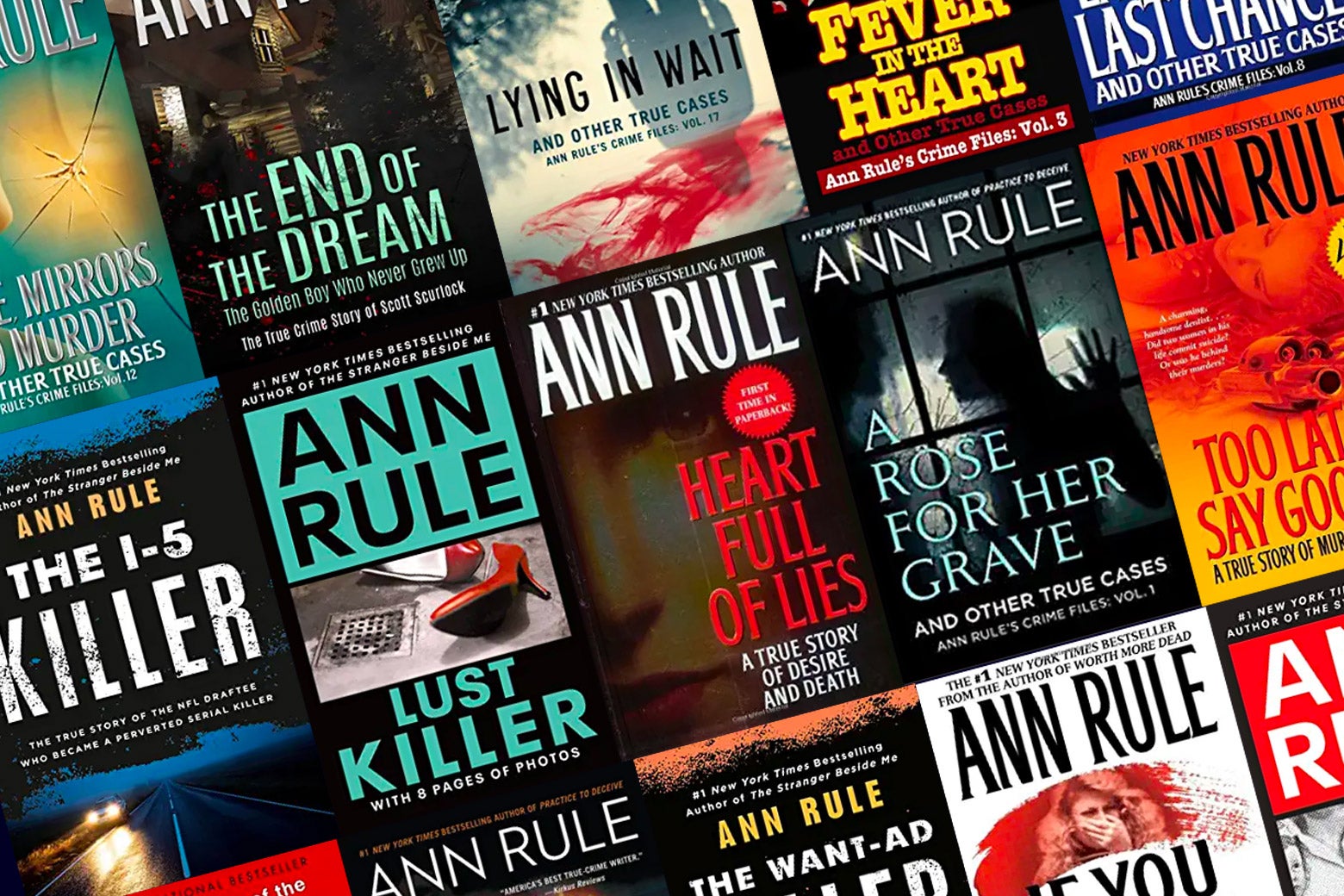

Rule died in 2015, just as the podcast Serial was ushering in a new, more prestigious era of true crime. In Rule’s day, sure, people could point to Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood, a moody tale of senseless butchery and sublimated homoeroticism in the sere light of the Kansas prairie. In 1979 Norman Mailer’s The Executioner’s Song further demonstrated the legitimacy a marquee literary name could bring to an otherwise lowbrow genre. But if In Cold Blood served as the genre’s aspirational pinnacle, the books Rule cranked out represented its seedier, densely populated, highly profitable valley. She was fantastically successful and widely read, but she published books with titles like A Rose for Her Grave that screamed their lurid, foil-stamped premises (“A Woman’s Fury, A Mother’s Sacrifice”) from the mass-market paperback racks in drugstores. Hers may be the standard that high-minded true-crime storytellers now aim to rise above, but today’s murder podcasts and documentaries nevertheless owe a huge debt to Rule for the way she transformed the genre, from exploitative newsstand fare to the bookshelves of America’s well-appointed living rooms. Rule changed who read true crime—and sowed the seeds for the new generation of real-life tales of investigation.

What often gets lost in the short version of Rule’s rags-to-riches tale was that she was already a true-crime writer when she met Bundy. Through the 1970s, Rule, the divorced mother of four small children, supported her family by writing magazine articles, at first for women’s publications but eventually as a stringer for True Detective magazine, covering the Pacific Northwest, where she lived. According to the New York Times, Rule wrote two 10,000-word stories per week for 13 years—all published under male pseudonyms, mostly Andy Stack—a staggering amount of work, given that she was also researching and writing books (as well as raising four kids). One of those books was about a series of murders of young women in the Seattle area, and Rule had even informed the police that she knew a man who answered to the description of the main suspect, but it wasn’t until Bundy was arrested for kidnapping in Utah that the truth about her old friend properly dawned on her.

Bundy was, of course, the story of a lifetime, and one that had to be published under Rule’s real name. Rule’s articles written as Stack—those articles, plus three books published under his name before her name became so famous that her publisher reconsidered—make an illuminating contrast to Stranger, and the books she wrote and published under her name in the years afterward. These differences mark the beginning of a major shift in the audience for true crime.

True Detective began its storied run in 1924 as a pulp magazine focusing at first on mystery fiction but soon shifting to meet its readership’s demand for true crime. At the magazine’s peak in the 1940s, it sold 2 million copies each month. And who were those 2 million people? The cover art offers a clue. While the design style changed with the times, the basic motif remained constant: Nearly every issue featured a pinup beauty, often scantily clad, being menaced by a sinister attacker. Browsing through back issues turns up ads for baldness cures, Charles Atlas bodybuilding programs, and assistance for “men past 40 who are troubled with getting up nights.” In short, although demographic data about True Detective’s readers isn’t (and probably never was) available, the magazine’s advertisers clearly believed its audience to be male. So, presumably, did its editors, seeing as they asked Rule to pretend to be a man. Today true crime is widely viewed as a genre appealing to women, who make up the majority of true-crime podcast listeners and fan convention attendees. How, exactly, did this happen?

The October 1970 issue of True Detective features an Andy Stack story, unforgettably titled “I Have a Problem … I’m a Cannibal.” In some aspects, the piece is identifiably Rule’s. It includes the methodical accounting of police procedure so popular with the magazine’s readers and carried on through the many books Rule would write in the decades to come. Sometimes the article reads like (and was possibly in part copied from) official police reports: “Investigation disclosed that the Opel was registered in the name of James Michael Schlosser, 22.”

This was the ideal True Detective formula, a stoic recitation of police procedure mixed with a touch of action and more than a touch of shameless sensationalism. At times the story is as breathless as a dime-store paperback: “Then … he tore out the dead man’s heart and ate it!” It describes a world in which, for example, “clean-cut, average boys” transformed into “men who favored a ‘hippie’ appearance with long hair and beads and medallions” and murdered a kindly social worker—but, beyond some hand-waving in the direction of “devil worship,” Andy Stack doesn’t waste much time wondering what makes people commit such horrid acts. For True Detective, the priority was clearly to include as much of the gory details and crime scene photos as possible.

The three serial-killer books Rule wrote as Stack mostly follow this formula. In The I-5 Killer, for example—about a former football player turned armed robber, rapist, and murderer—Rule recounts the abuse Randall Woodfield inflicted on his victims in considerable and nauseating detail. In The Stranger Beside Me, however, the most revolting of Bundy’s activities go undescribed. Perhaps this decision was strategic: If you tell your reader about Bundy having sex with corpses and keeping his victims’ severed heads as souvenirs, they’re going to care less about the emotional fluctuations in your friendship with him—in fact, they’re going to start wondering how you failed to notice what a gargantuan freak he was. Nevertheless, one effect of Rule’s choice to play down the gore and delve deeper into personality and relationships was to make the book more appealing to women readers than the True Detective–style stories she’d been writing. In the aftermath of the 1970s, when the familiar fabric of society felt increasingly frayed, what woman couldn’t relate to a story about a seemingly perfect man who turned out to be a secret fiend?

It’s no surprise, then, that after the success of The Stranger Beside Me, Rule would mostly steer away from grotesque serial killers. (With one exception: In 2004’s Green River, Running Red, she wrote about Gary Ridgway, the Green River Killer, but for Seattle’s preeminent true-crime author, that was basically obligatory.) Instead, Rule gravitated toward stories in which homicide erupts into the seemingly perfect lives of middle-class white people. In 1991 she published If You Really Loved Me, about a wealthy entrepreneur who manipulated his teenage daughter into killing her stepmother. In 1997’s Bitter Harvest, a woman physician poisons her husband and sets fire to the family home, causing the death of two of their children. In 2001’s Every Breath You Take, a woman is murdered by her obsessed ex-husband.

In a 1994 interview with the Guardian, Rule characterized herself as a “psychological detective,” primarily interested in the “psychopathology of the criminal mind,” but there was one kind of criminal that truly fascinated her: a privileged person, someone whom her readers might otherwise identify with or envy, implicated in a horrific homicide. The last thing her readers wanted, she assured her interlocutor, was murderers who were “ugly, mean and have no charm. We’re not interested in the kind of person who looks like he would commit murder. We want to know about the kind who you could not imagine having this monstrous self behind the pleasant face.” The subject most closely associated with her, Bundy, presented just such a pleasing appearance, and aspired to the trappings of a cultured, affluent life. (The Stranger Beside Me features so many references to Chablis.) It was his facade, not his perversions, that made him compelling to Rule.

All this is a far cry from the simple toughs, bums, and degenerates who served as the favored villains in the pages of True Detective. In Rule’s hands, true crime became a genre about the secrets kept by families, the violence lurking behind displays of domestic contentment, the conflict between individual selfishness and the communal demands of marriage—all subjects about which women and girls have intimate knowledge. Even when the perp was some psycho, Rule tried to explain how he or she got that way, and if these efforts sometimes come off as crude and quasi-Freudian—his mother used to dress him up as a girl, his sisters used to boss him around, etc.—they were more than the pulp magazines bothered with. As her books made bestseller lists, other authors and publishers followed suit—with such titles as Bella Stumbo’s Until the Twelfth of Never, about a woman who killed her ex-husband and his new trophy wife, and Evidence of Love, by Jim Atkinson and John Bloom, about the Candy Montgomery case. Though serial killer books (written mostly by men) remained popular, the success of Rule, and the authors who followed her lead, began to make true crime less of a guy thing and more of a chick thing—expanding beyond cops and robbers to ruminate on hearts and minds.

Yet in one respect, her work remained firmly old-fashioned. Several of Rule’s male family members worked in law enforcement, and her own provisional stint at the Seattle Police Department was cut short only because she failed an eyesight exam. You could argue that Rule’s rapport with and acceptance by police and prosecutors was even more essential to her long-term success than her friendship with Bundy was. Her many law-enforcement contacts fed her a steady stream of story leads and provided her with exceptional access. The books reflect this coziness with law enforcement: Occasionally the police departments in her stories make mistakes or act too slowly, but their good faith is never questioned. They were her sources, and Rule identified closely—too closely—with them. Rule’s is a world familiar to anyone who watches network TV, filled with dedicated detectives obsessed with doing justice to victims and haunted by the perps that got away. In this world, the possibility that law enforcement might be biased, self-interested, incompetent, or just plain lazy is unthinkable.

There’s still plenty of lurid, slapdash true-crime content out there, from the offensively flippant to the flagrantly unethical. Rule’s formula—exposing the ugly transgressions hiding behind respectable fronts—has been so widely adopted by everyone from the Lifetime channel to the Investigation Discovery network that it’s now what many people think of first when they think of true crime. But the creators who have led the recent true-crime resurgence—podcasts like Serial, In the Dark, Missing and Murdered, and Undisclosed; documentaries like West of Memphis, The Central Park Five, and Murder on Middle Beach; and books like Lost Girls, Unbelievable, and Just Mercy—have been more daring in their willingness to question the criminal justice system and those who work within it. Systemic bias based on race, class, and other traits, never acknowledged in Rule’s work, has become a recurring theme, as have such common phenomena as false confessions and wrongful convictions. Rule may have built the female audience for true crime—how many teenage babysitters first discovered the genre while browsing the bookshelves of their employers?—but her unquestioning faith in the police now makes her work feel hopelessly dated. (On the other hand, Rule’s choice to focus on unambiguous cases means that the substance of her work has not been continuously relitigated, like Serial’s take on the Adnan Syed case.)

The fact that Rule’s flavor of true crime has become a cliché of cheesy cable-network docudramas or that it spawned its own set of crime-coverage clichés doesn’t invalidate the way she opened the genre’s eyes to the family as a place where violence occurs. Her commitment to writing books only about cases that had been “solved” left her oblivious to crime’s many ambiguities, and gives her work a flatness that feels of a piece with her lusterless prose. The best of the new breed of true crime is more comfortable with uncertainty. It often points to how the need for speedy and simple solutions can end up perpetrating even further injustice. But look closely at the kind of true-crime writing once published in True Detective, and it’s impossible to see how we got to Serial without Ann Rule.

Shortly before Rule’s death, her two adult sons were charged with theft, forgery, and domestic violence by King County prosecutors, who accused them of abusing and exploiting their ailing, elderly mother to extract money from her. Ann Rule had spent most of her career warning other women about the “monstrous self behind the pleasant face.” But even she could not escape this final betrayal. As naïve—about the police, about psychology, about the larger forces that shape crime and criminal justice—as Rule’s books can seem now, after decades of social change, she got that one thing right: We’re the most vulnerable where we most trust.