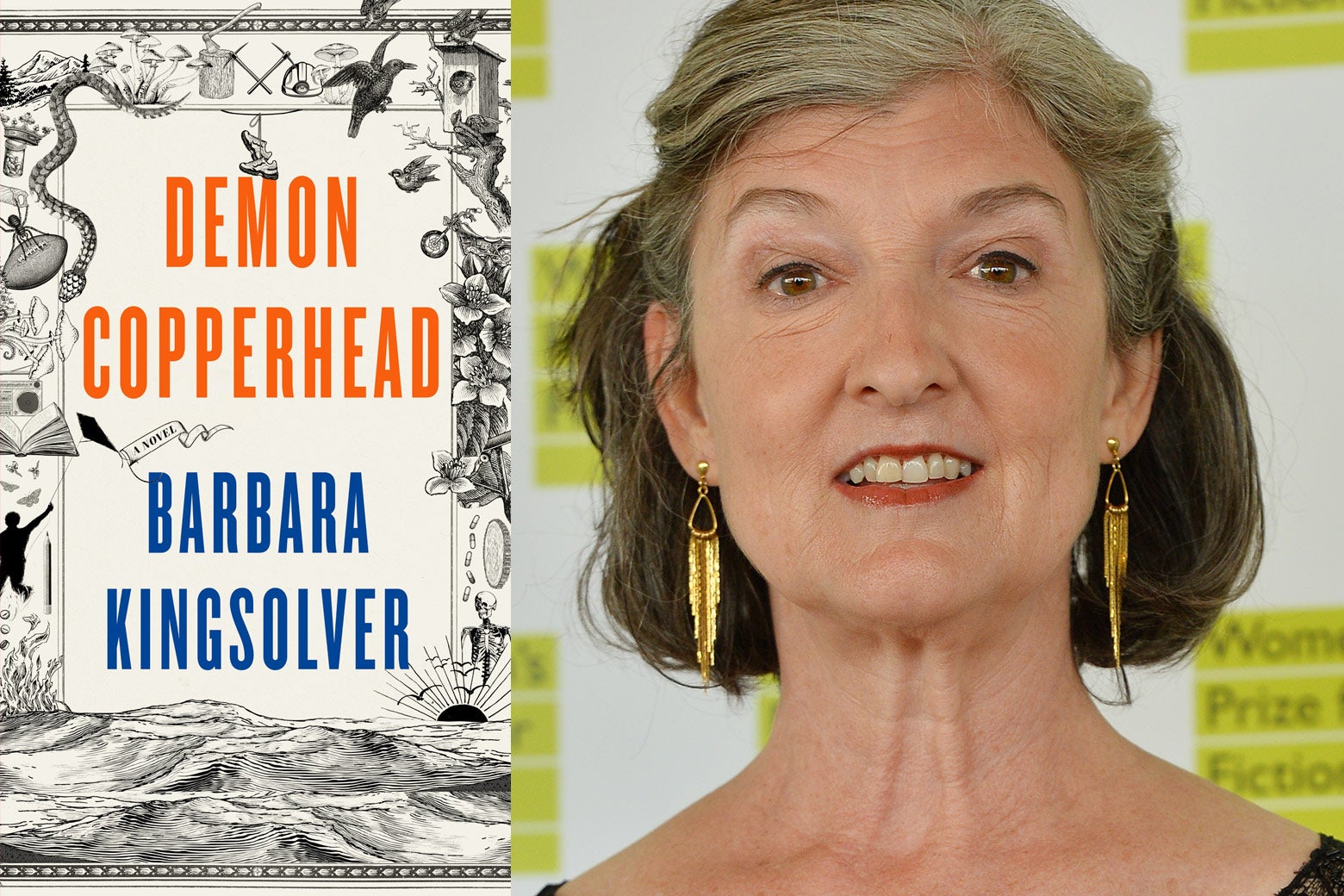

Gabfest Reads is a monthly series from the hosts of Slate’s Political Gabfest podcast. Recently, Emily Bazelon, David Plotz, and John Dickerson spoke with author Barbara Kingsolver about how Charles Dickens came to her before she wrote her new novel, Demon Copperhead.

This partial transcript has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Emily Bazelon: Demon Copperhead is a recasting of David Copperfield, the classic novel by Charles Dickens. And Barbara, you’re following the path that Dickens laid out to tell the story in his time of a boy growing up in 19th-century England, and you are telling the story of a boy growing up in our times in Appalachia. I’ve wanted to ask you for so long, why Dickens as your source of inspiration? I especially want to know this now because I was reading a recent essay in the New Yorker by Zadie Smith, and she was disparaging Dickens as being too sentimental, too theatrical, too moralistic, and too controlling. And it just made me so curious because you have sought him out as a source of material and inspiration. Why is that?

Barbara Kingsolver: He showed me the way into a story that I had found impossible to write for several years. I spent close to three years absolutely sure that I wanted to tell the story of what’s happening to my community, our communities, here in Appalachia as a result of the opioid epidemic. I wanted to tell the bigger story, sort of the whole historical context of how this region has been exploited by big capital for centuries, and how that has shaped the identity of this region and how it has created institutional poverty here. It has suppressed our culture of education. It has done all kinds of things that we Appalachians get blamed for.

I think that outsiders look at this region as backward, this whole hillbilly stereotype of these shiftless people who lack the ambition to get a proper education and pull themselves up by their bootstraps, et cetera. These are my people. I’m Appalachian; that’s my identity. This is home. This is the place and these are the people that I love who make me who I am, who make me happy to be alive.

The story I wanted to tell was about the orphans—really literally the orphans of the epidemic, of whom we have an entire generation here coming up through our school system—how little is being done for them and how these are the throwaway kids of a very wealthy society. Who wants to hear that story? I just really felt blocked. I couldn’t find a way in.

And then through a very strange circumstance, I had a visit from Dickens, this sort of ethereal visit in his house in Broadstairs, and he told me to tell this story. He said, “Look, nobody in my time wanted to hear about these orphans either, and I made them listen.” I sat up and took note. And what he told me is, “Point of view is your tool. Let the child tell the story.” And I started writing it that night on his desk, the desk in his house at Broadstairs where he wrote David Copperfield.

Listen, OK, Zadie Smith has her opinion about this guy who is too sentimental, too moralistic, too uncool, and that is all fine and good. I love Zadie Smith and I think she does great work. But let me also tell you that when Dickens wrote his novels about structural poverty and orphans and these stories nobody wanted to hear, they were lined up on the docks to get the next installment of the story when they were delivered by ship.

So, I think the bottom line here is a crackerjack plot, really great characters, and point of view. Let the kid tell the story. I needed to make this a galloping tale. I needed to make it funny, memorable, fast-paced, all of those things, and use the tools that Dickens gave us to make this a story that people would read. That gave me confidence. And I’ll also say that my story is substantially less sentimental than David Copperfield. David Copperfield, bless his heart, is this wide-eyed, this kind of starry-eyed kid, who says, “Wow, mommy has a new boyfriend. Hope he’ll be nice.” Well, my David Copperfield, my Demon, he’s on to this guy. The day he moves in, Demon says, “Nope, this is not going to be good news.” So, he is just a lot more savvy. He’s a 20th-century and 21st-century kid. He can’t be as naïve. Not that any kid now can be quite that naïve, but especially one who’s been basically taking care of his own mother since he was out of diapers.

David Plotz: That was such an inspiring answer, Barbara. As a child, my father read David Copperfield to me, and so I’m acutely aware of how vivid the dialogue is in that book. I think what’s incredible, my girlfriend was just listening to Demon Copperhead as an audiobook, and you’ve done an amazing job in capturing the voices of the people you’re writing about. I just am interested in what your process was to do that? How did you channel that language and kind of invent this—I mean, I guess you didn’t fully invent, but there was some act of creation of this voice of Demon, which is amazing voice.

This is my native language. I grew up listening to Appalachian talk. What you’re hearing from me right now isn’t exactly Appalachian vernacular. I code-switch, and I learned very soon after I moved from Appalachia that if I talk the way I grew up talking, people would have their opinions of who I am. And I gradually developed another sort of affect that I present to the outer world so that people would stop making fun of the way I pronounced words and listen to what I was saying. But I could kind of gradually bring you into those waters, ultimately surround you in the bath of what I think is a beautiful language so that you could appreciate it, but I just didn’t dump you into the deep end of that, well, bathtub, to reuse a very old metaphor.

For example, there are words that are sort of triggers for people’s judgment. The word “holler.” The word “reckon,” I reckon. Which is so interesting, because when British people or Australians say, “I reckon,” that sounds high-class. But when I say it, “I reckon,” you just put the straw hat on me in your mind. So, I could ease you into it.

One thing that I absolutely hate in printed books is what I call “Uncle Remus spelling,” where people use misspelled words to represent vernacular pronunciation. You know what I’m talking about. I hate that because it’s condescending. When we speak, our language here is—obviously there is substandard speech, but it isn’t wrong to say, “I reckon he’s gone up there in the holler.” There’s nothing wrong with that. So, I’m not going to misspell things and suggest otherwise. But I will tell you, the first draft, I got about 200 pages in, and then just for curiosity I did a search: “How many times has Demon dropped the F-bomb in the first 200 pages?” And the answer was like 175 times. It was probably too much. And other things. His anger toward outsiders, judgment of his people, all of these things were too ratcheted up in the beginning. So, I had to really think about, through draft after draft after draft—because that’s the way I work—really shaping that voice. I really want you to want to adopt this kid, to get you on his side. And then by the end, I think you’re probably just as mad as he is at the way our country has failed him. And that’s the goal.

But it’s just, how do you do it? You just do it. That’s the work. That’s what I do at this desk every day is work and work and work and redraft until the voice just is as clear on the page as it is the way I hear it in my head.