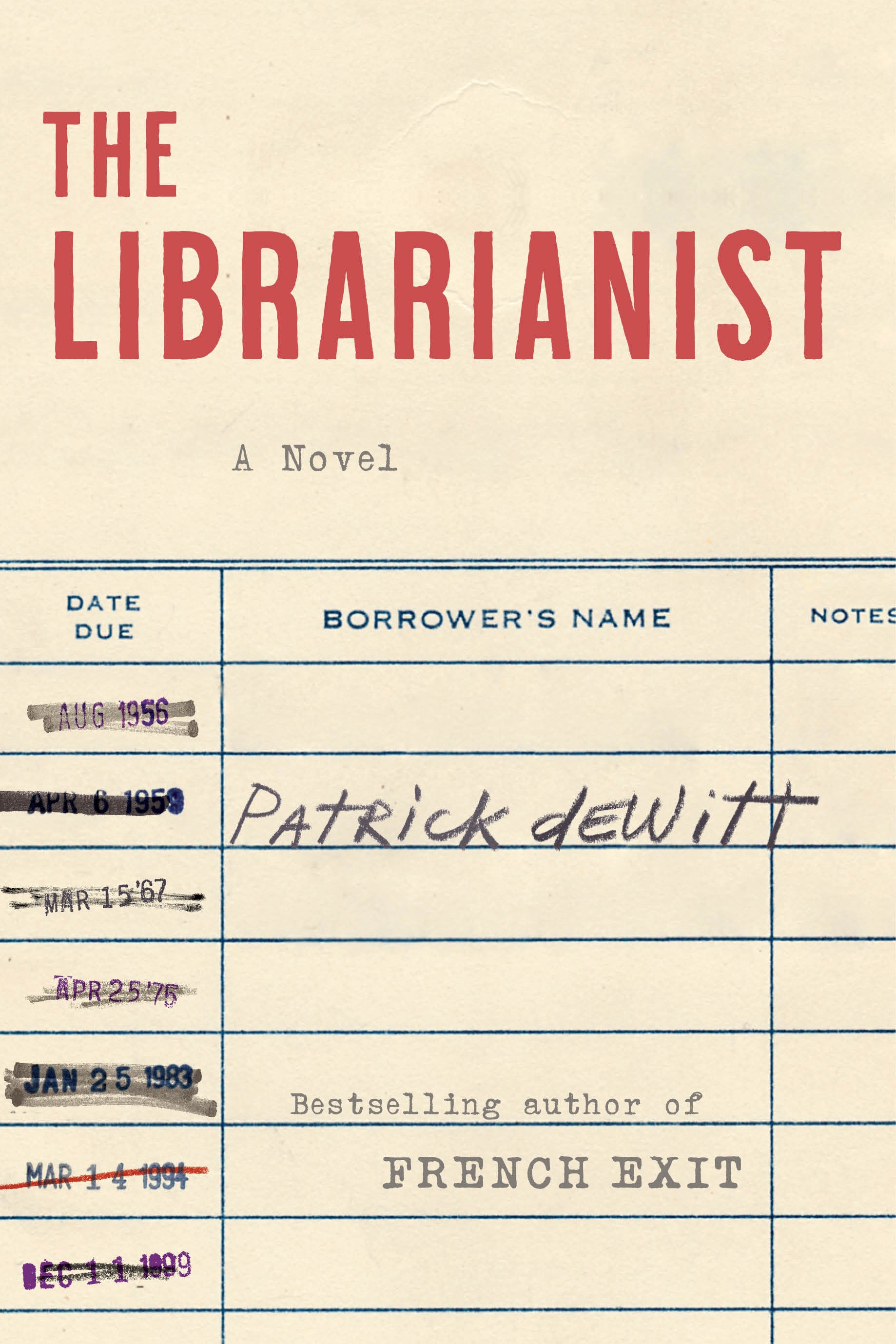

In another, even less satisfactory timeline than our own, The Librarianist, Patrick deWitt’s new novel about an introverted bookworm making a late-life bid to belong, would have a much sweeter center and a very different title. It would be called something ornate, featuring the main character’s three-syllable, faintly antiquated surname—something like The Five Secret Lives of Waldo Murgatroyd or Henry Fitzpatrick Takes the Bus. It would be a misty-eyed paean to the cozy pleasures of reading and the fragrance of old books. It would be very popular with librarians.

Librarians will probably be annoyed by The Librarianist, whose title character, the unmeteoric Bob Comet, conforms to every stereotype of the breed: methodical, reserved, staid. The novel opens in 2005, with 71-year-old Bob—retired after 45 years working in the same Portland, Oregon, branch library—now spending his days walking and reading, dreaming of a seaside hotel he visited just once, at the age of 11. Unmarried, solitary but not exactly lonely, Bob can’t figure out why the dream is suffused with an emotion exactly like “the onset of profound romantic love,” despite the fact that he hadn’t fallen in love at the Hotel Elba. The dream arrives like a bit of atmosphere, the melancholy reflectiveness of an old man’s waning years, but it is really the novel’s central question: What did Bob Comet find at the Hotel Elba and then yearn for the rest of his life?

Slate receives a commission when you purchase items using the links on this page. Thank you for your support.

The Librarianist is a gentler work than deWitt’s best-known novel, The Sisters Brothers, and the two books that followed it, French Exit and Undermajordomo Minor, each one an elegant vamp on a particular literary genre—the Western, the comedy of manners, and the gothic—with plenty of sharp edges. His first novel, Ablutions, based on his experiences tending bar at a fading Hollywood watering hole, established the essential, abiding signature of his fiction: its easygoing habit of allowing itself to be hijacked by characters who are just passing through, each with his own tale to tell. The effect is very much like hanging out at a bar and being buttonholed by a series of eccentric regulars.

It’s very American, this form of storytelling, reminiscent of Mark Twain, the writer deWitt resembles most. Initially a journalist, Twain never entirely abandoned the notion that his job was to wander around collecting and recording the yarns of people on the fringes of an adolescent nation. This anecdotal style suits a society of transients who wash up together of an evening, share their remarkable experiences, and then move on. It’s a mode suited to tall tales and one version or another of sales pitches, some sketchier than others.

Bob Comet, though: He’s not the kind of guy likely to have such encounters. He doesn’t go to bars, and his social life consists largely of glimpsing other people’s lives through their front windows and hoping for some exciting event like a house fire. Bob, deWitt writes, “had long given up on the notion of knowing anyone, or of being known. He communicated with the world partly by walking through it, but mainly by reading about it.” If The Librarianist were the sort of novel I described earlier, Bob’s reticence would be regarded fondly, as a sign of sensitivity requiring only that he find—perhaps through the intermediary of a precocious child or a mischievous animal—similarly tender, bookish souls with whom to commune.

But The Librarianist is not actually a book about books and the fine qualities of the people who love them. Books seldom feature in the novel, and when they do, they’re typically inadequate to Bob’s needs. When Bob encounters a stray, catatonic resident of a nearby senior center in the 7-Eleven and shepherds her back, he offers to volunteer there. His big idea is to read to the residents, beginning with Poe and moving on to a selection of Russian authors. (“Everybody likes to be told a story,” he explains to the center’s frazzled manager. “Okay, but do they?” she replies.) He prefaces his Russian readings with a talk about how “We read as a way to come to grips with the randomness of our being alive. To read a book by an observant, sympathetic mind is to see the human landscape in all its odd detail, and the reader says to him or herself, Yes, that’s how it is, only I didn’t know it to describe it. There’s a fraternity achieved, then: we are not alone.” This overly familiar sentiment makes no impression on his inattentive audience. To Bob’s dismay, they mostly wander out of his reading before he finishes.

The manager suggests that Bob simply show up every day, that his simple but constant presence might be more comforting to people “in a state of letting go” than high-flown declarations of the power of literature. He gets to know an ugly man who used to be very handsome and a woman convinced that her space heater is an “oracle” foretelling her eternal damnation. These friendships, and a startling revelation about the catatonic woman Bob rescued from the convenience store, prompt a series of flashbacks to the death of his unmarried mother in the 1950s, to his brief courtship and marriage a few years later, and finally, to his four-day adventure as a runaway at the Hotel Elba in 1945.

The first two of these flashbacks exquisitely illustrate Bob’s distance from the people in his life. Even when living in the same house as his mother and then his wife, he always seems to be watching them through a window from the outside. Bob’s great fear, as he falls in love with Connie, a young woman he meets at his library, is that she will in turn fall for his only friend, the charming and catastrophically handsome Ethan. As with most great fears, this one has a way of making itself come true. The Librarianist offers no firsthand account of the romance that kindles between Connie and Ethan, just interactions that Bob glimpses from a distance, small gestures, inexplicable shifts in mood, the implied significance of a bit of red string. The reader can only imagine how the pair resist and then succumb to a love that forces them to betray a man they both cherish, and it is enough to break your heart.

The Librarianist becomes truly Twainian—and deWittian—in its third flashback, as the 11-year-old Bob runs away from home and meets a pair of women en route to the Hotel Elba. There, the traveling “thespians”—deWitt makes the most of the suggested rhyme here—plan to stage a performance involving a full-size guillotine, trained dogs, and witch costumes. At the hotel, Bob will meet an antisocial horticulturalist, a lovelorn chambermaid, and an ironical sheriff, each given a moment to belly up to the novel’s bar and take over. But it’s June and Ida, the thespians, who are the true stars here, an homage to the Duke and the King from Huckleberry Finn, but a benign one. Two of deWitt’s novels, The Sisters Brothers and French Exit, have been made into indie films, with deWitt writing the screenplay for the latter, and you can see why. No one writes loopier, funnier dialogue:

Ida told Bob, “She dreamed you were set upon by tramps.”

June scowled at Ida. “You know, Bob,” she said, “I support your project in every way. But I’m uneasy at the thought of one so young as yourself being alone in the world. Because the world sometimes is a complicated place.”

Ida said, “You always hear about tramps buggering children.”

“Ida, Ida,” said June.

“What? You do hear about it. Forewarned is forearmed.”

June patted Bob’s arm. “You’ll not be buggered, Bob.”

“But if you are,” said Ida, “don’t say we didn’t warn you.”

DeWitt’s dialogue oscillates between an easy vernacular and old-fashioned flourishes (“one so young as yourself”), a style perfectly suited to the Western milieu of The Sisters Brothers, but that tends to give his other novels an unreal tinge. For all their dire warnings, however, June and Ida are much kinder than the ruthless and rude characters who have populated those earlier books. Even Connie and Ethan, who ruin Bob for the majority of his adult life, are agonized by their transgression. French Exit and especially Undermajordomo Minor are essentially satirical works, and The Librarianist is not. That doesn’t make it as sentimental as all those popular novels about curmudgeonly booksellers whose hearts are melted by true love and good friends, but the warmth that deWitt exhibits here gives this one an emotional staying power his earlier books lack.

Is it possible to change the contours of your personality late in life, with, as the woman with the prophetic space heater puts it, “the knowledge of a long dusk coming on”? The final scene in The Librarianist features an answer as modest as it is revolutionary, but deWitt has spent the preceding pages making the oxymoron of a modest revolution utterly believable. The answer is: maybe a little bit. Maybe enough.