In the concluding chapter of his new book, The Country of the Blind, Andrew Leland, a writer and audio producer, likens himself to Clov, a character from the play Endgame, who speaks the line “Finished, it’s finished, nearly finished, it must be nearly finished.” It’s never a good sign when you feel like a Samuel Beckett character, but the comparison is apt. Clov is the partially blind servant of a cantankerous, fully blind man, and Leland is a partially sighted man who has written a book about blindness and blind culture. He has an inherited condition, retinitis pigmentosa, that causes the slow deterioration of the retina. He expects to be completely blind someday, but no one can say exactly when. Leland can’t see well enough to drive—he is legally blind in Massachusetts, where he lives with his wife and son—and uses a cane to navigate sidewalks, but he can still see an annoyingly “helpful” fellow pedestrian well enough to describe her as “an eccentric-looking woman in an ankle-length brown coat.” He writes that he lives in an “infinite endgame, a frozen twilight where I’ve gone blind but still can see. Then another grain of blindness is added to the heap.”

The Country of the Blind is a familiar hybrid of genres in which a writer describes his own experience of a particular phenomenon, then expands on it by traveling around, interviewing various experts, then reflects on how what they’ve told him has enlarged his understanding of his own situation. Researching the book took Leland to a convention of the National Federation of the Blind in Florida, a gallery in Manhattan showing the work of the blind painter and sculptor Emilie Gossiaux, a shop that produces audio descriptions of film and television, the Bay Area office of the principal accessibility researcher at Amazon (a MacArthur “genius grant” fellow), and finally to the Colorado Center for the Blind, a residential training school where students learn “how to read braille, use screen readers, cook meals, sweep floors, cross busy streets, even use power saws in on-site woodshops.” On that last trip, he donned sleep shades that blotted out the tunnel vision he retains so that he could practice the skills he may (or may not) need someday.

A fluid, thoughtful writer, Leland finds plenty of fascinating insights during these journeys. Dismissing the cliché that the blind compensate for the absence of sight by developing preternatural senses of hearing, he nevertheless finds himself, behind the sleep shades in Colorado, experiencing “mildly psychedelic,” synesthesia-like responses to the aural landscape in the center’s cafeteria. When someone brought in a toddler, the child’s babbling “cut through the room like washes of color.” He recounts a fellow writer’s initially unsettling experience of using a screen reader to repeat back to him the words he’d just typed. When “sighted people read,” the man said, “they have a voice in their head. I don’t have one. I haven’t had one for years because I never read for myself.” Leland meets a sighted man who once had a job reading for a blind retired philosophy professor. “He wanted someone good at reading junk mail,” the reader explained, a seemingly mystifying requirement until Leland realizes that he craves the same access to trash as well as to quality: “the freedom to know the unspoken on-screen URL in the TV ad for the weird fitness product that I feel ashamed of being interested in. I want to watch what everyone else is watching, even if it’s a soul-crushing training video, or a bad sitcom, or an ad for paint.”

At heart, The Country of the Blind is a book about identity, which in Leland’s case is a strangely fluctuating proposition. Among blind people, he can see fairly well, but among the sighted, he is more blind than a casual observer might realize. (Encounters with suspicious strangers who accuse him of not really needing his cane are not uncommon.) Because he evidently moves in politically progressive circles, this puts Leland in the position of sometimes feeling entitled to claim a marginalized identity that brings with it a certain amount of rhetorical authority—he can be indignant over patronizing remarks made by sighted people—and at other times obliged to mince around the minefield of contemporary identity discourse.

In chapter titled “The Male Gaze,” for example, Leland describes the way his impending blindness complicates his feelings about his masculinity and sexuality. He plays this delicately and partly for laughs, musing about how ineffectual he’d be at protecting his family in the event of a zombie apocalypse. A book he found “more terrifying than any episode of The Walking Dead, easily the scariest book I’ve read” is a memoir by the Australian theologian John Hull, who also lost his vision in midlife and meticulously recorded the effect of this on his emotional landscape. Hull described a dampening of his libido after he became unable to see, as well as a nagging, guilty curiosity about what the women he met looked like. Leland himself, when asked the irritating question of what he will most miss when his vision goes, used to joke by first listing artistic and natural wonders, then adding, “and butts, sheathed in that modern denim that somehow stretches like yoga pants.”

The joke, Leland reports, never went over well, so he stopped telling it. The male gaze—his professor wife reminds him, as he strives to disentangle what seems like a legitimate sense of loss from some sort of privileged transgression—“fixes women in an acquisitive, objectifying light, and it’s from this kind of entitled, invasive looking that systemic violence arises.” True enough, but it is fully possible to appreciate the desirable appearance of other people without being a dick about it. There’s an intractable sadness running through this chapter—as well as some unexplored aspects of male sexuality—that Leland can only pass over on his way to the safer territory of discussing how, when on trial, notorious sexual predators like Bill Cosby attempted to use their own visual impairment as proof that they were not virile enough to commit those crimes.

As a writer, Leland is more cerebral than sensual, so it’s frustrating when his ability to fully examine his experiences and ideas feels a bit hemmed in by this fear of stepping out of line. The sweet spots in The Country of the Blind—and there are lots of them—come when his efforts to comprehend something intellectually tips him over into unexpected emotion. As someone who has “always looked at art with a cooler eye, as something that was interesting to talk and think about,” he surprises himself by tearing up at Gossiaux’s drawing of guide dogs dancing around a white cane as if it were a maypole. (She draws by touch, using crayons and a rubber mat.) She had found joy in aids that he’d previously regarded with a muted dread.

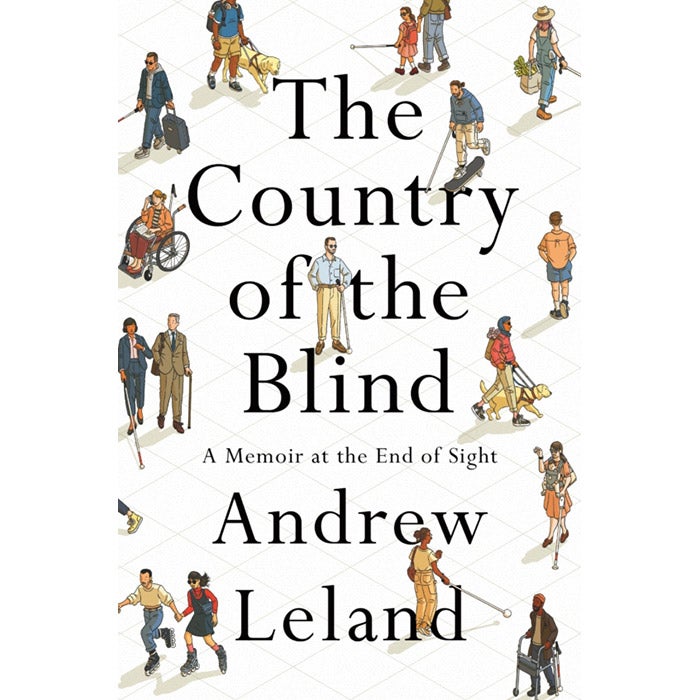

The Country of the Blind

By Andrew Leland. Penguin Press.

Slate receives a commission when you purchase items using the links on this page. Thank you for your support.

The historical passages in The Country of the Blind are less compelling, with the exception of a chapter on the birth of the disability rights movement in Berkeley that zips and sizzles with the marvel of human ingenuity and resourcefulness. Even the saga of the National Federation for the Blind—an organization rich enough in feuds, scandals, and controversies to become a sort of character in its own right—is less interesting than Leland’s puzzling out of his own flickering evolution. It is true that he faces great losses, chief among them the image of the beloved faces of his wife and child, but there are gains too, and he makes a convincing account of them.

At a natural history museum, Leland’s son, Oscar, describes for him an exhibit of a stuffed owl, saying, “The talons are like this,” and the father reaches out to feel the boy’s hand in the shape of a claw. The intimacy of this, and the practical necessity of walking around the exhibits hand in hand, is an experience neither of them would have had if he were sighted. It makes Leland feel as if he had “unlocked a new, airy chamber in my life as a blind person.” The Country of the Blind is itself such a chamber, full of riches where he had anticipated only deprivation, and with plenty of corners yet to be explored.