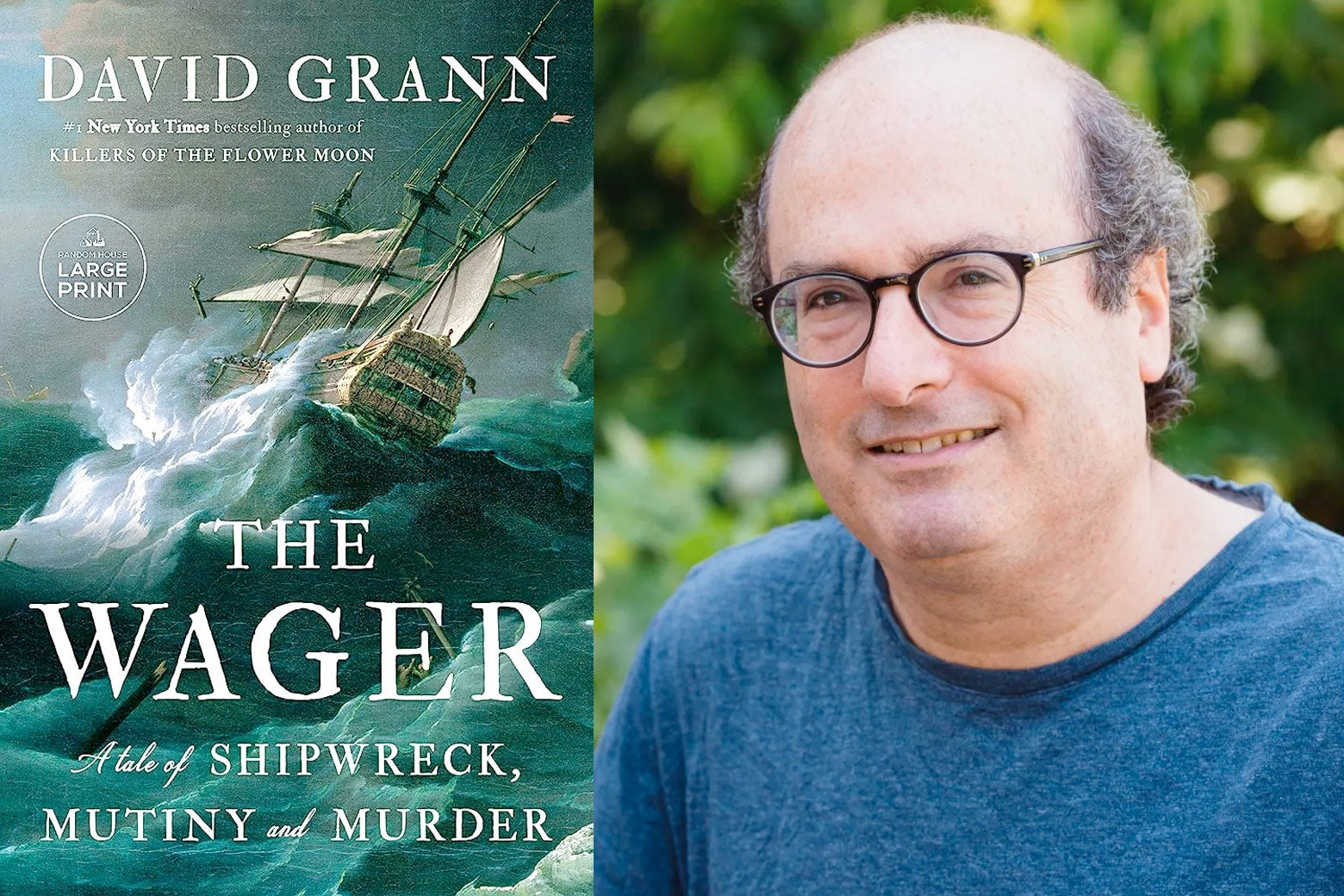

Gabfest Reads is a monthly series from the hosts of Slate’s Political Gabfest podcast. Recently, David Plotz spoke with author David Grann about the extensive research necessary to complete his shipwreck novel, The Wager.

This partial transcript has been edited and condensed for clarity.

David Plotz: This is a really interesting book because it’s this adventure story, but it’s also a story about how you tell your story. And you have reconstructed the story of The Wager from remarkable documents. Talk a little bit about how you tell this story. And also, how can you believe that the story you tell is true, given that it’s 280 years old and it’s these accounts that people are making for totally self-serving reasons?

David Grann: Yeah. I mean, the thing that really drew me—first of all, there’s this surprising trove of primary materials that somehow survived this expedition. The thing about the British Empire is they liked to record. They wanted to meticulously document things. And so there are these records, there are these logbooks and muster books and diaries and journals that survived this expedition. You go to England and you open up these boxes and you can literally pull these documents out.

What does it look like? Are you allowed to handle any of this stuff? Can you actually read it when you look at it?

You can read them. I mean, they come in a box. Often they have leather-bound covers that are disintegrating, like a covering, and just dust. Like when you open the box, dust just infiltrates your nose, your nostrils. You have to lay them on pillows because otherwise they will further disintegrate. You have to turn the pages so, so gently. Sometimes they are water-stained and a little bit rubbed out, but for the most part you can read them. Sometimes you need the help of a magnifying glass. But for example, the logbooks are meticulous records, day by day, of what happened, that would allow me to vividly reconstruct what happened.

And of course, it takes some experience to learn how to read these documents. For example, a muster book is just a listing of enrollment of when a person joins a ship, their name, their rank, but they’ll often have a symbol next to their name. I’m not a British naval historian; it took me a while to get used to these documents. I kept noticing there was a symbol next to their names. It kept saying—so many of them had the letters “DD,” just the capital “DD,” DD, DD. And I was like, “What is that?” And then eventually I learned that DD means “discharge, dead.” And so I realized that the muster book, which in some way seems like kind of gibberish, an anodyne document, really told the horrific toll on the voyage. I mean, you realize that nearly 2,000 people had set sail in this voyage, and when you do the tallies of the DD, more than 1,300 of them perished.

So, these documents speak, and they speak in these kind of startling, unexpected ways. But one of the things that drew me to this story is what you were saying. I mean, it’s just an incredible adventure story. It’s one of the more extraordinary sagas of survival and suffering and mayhem you might ever come across, but what was equally fascinating was what happened after several of these survivors incredibly make it back to England. And they are, after everything they have endured—shipwrecks, scurvy, starvation, violence—they’re summoned to face this court-martial and they could be hanged for their crimes.

Joan Didion famously said, “We tell ourselves stories in order to live.” And they quite literally have to tell their stories in order to live, because if they don’t tell a convincing tale, they may get hanged. And so they begin to release their journals and their testimony, or they write narratives, trying to shape the story out of self-interest, as you said, to try to save their own lives. And so I would be going to these archives and reading these disintegrating documents, and there would be this war over the truth. And there would be misinformation. You could read about allegations of fake journals, that people were faking the journals or plagiarizing the journals and rewriting them to serve different interests. And then, of course, I would come home, and I’d turn on your Gabfest; what would I be hearing? I’d be hearing talks about alternative facts and fake news.

And so I realized that this weird story had this incredibly surprising resonance with today. What I decided to do was to tell the story from the warring perspectives, three members of the expedition. One was the captain, David Cheap, one was the gunner, John Bulkeley, and one was the young midshipman, John Byron. And what’s interesting is they don’t lie so much, they don’t disagree over the basic facts. If someone was killed, they were killed. They were shot by this person. But the way they tell their stories is true to the way many of us tell our stories: they shape them and burnish them and edit them and revise them. What do they leave out of their stories?

And you can tell that. I’ll just give you one very glaring, vivid example. One person may describe on the island, in his account, he’ll say, “I was forced to proceed to extremities.” And then if you look at the account from John Byron, he’ll write, “Oh yeah, he shot him right in the head and he bled out in my arms.” And you begin to get a better sense of where the reality lies. So hopefully by reading the three accounts, you learn how we shape stories to serve our own self-interest, and I think you get closer to the truth, but I really try to leave it to the reader to interpret and offer that judgment.